Namespace/Container Resource Limits

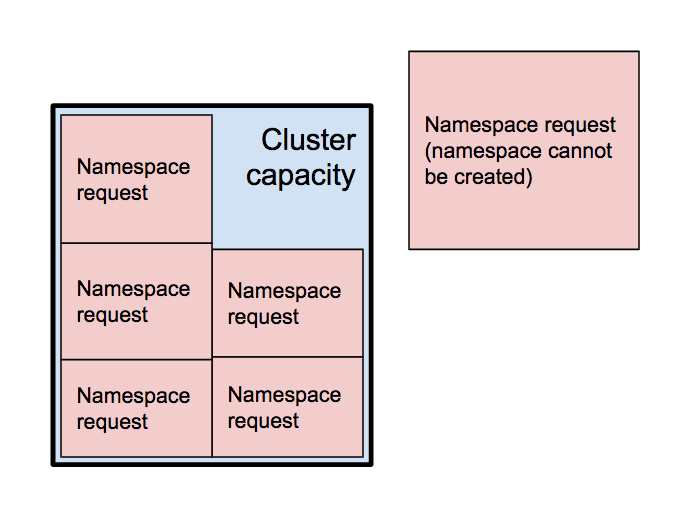

The cloud platform is a single kubernetes cluster, hosting multiple different MoJ services. So, the cluster capacity (in terms of memory and CPU) needs to be shared efficiently between the different services.

The smallest unit of work we ask the cluster to manage is a container, and the largest is a namespace. The cluster has several worker nodes, which supply the memory and CPU capacity on which workloads can run. So, kubernetes has to solve a classic packing problem - run a bunch of different workloads on the cluster, putting them on different worker nodes in the most efficient way possible. But the cluster can’t be sure in advance how much resource (memory and CPU) any given container is going to need.

To help with this, we specify request limits.

This article will use “request” because that’s the official kubernetes term, but request is a slightly awkward term here. It might be better to think of “reserving” rather than requesting resources.

Essentially, a request limit says to kubernetes, “this thing is probably going to need this much memory and this much CPU in order to do its job.” So, whenever it encounters a request limit, the kube-scheduler sets aside that amount of memory and CPU, and ring-fences it so that it’s guaranteed to be available.

The other kind of limits in kubernetes are known as hard limits. These are important at runtime, as opposed to request limits, which are important for the scheduling decisions the cluster makes before your workloads start to run.

The name “hard limits” suggests these are limits that kubernetes will enforce, so that the workload will be terminated if it exceeds them. The reality is a little more nuanced.

If the cluster has capacity available on the node where the workload is running, it may allow it to consume more resources than the hard limit specifies. But it will flag the workload such that, if the node runs out of resources and kubernetes needs to evict pods, the pods from the offending workload will be first in line to be evicted.

For simplicity’s sake, you can just think of a hard limit as meaning what it sounds like - the maximum amount your workload will be allowed to consume before bad things start to happen.

For the remainder of this article, we’re only going to talk about request limits, since those are what is relevant for scheduling workloads onto the cluster.

Memory versus CPU

Memory and CPU are the two types of resources we need to consider, and we’re going to pretend, for the rest of this article, that they’re handled in the same way. The truth is that they’re not. If a workload tries to consume more memory than is available, it may be terminated by the cluster (‘out of memory killed’, aka OOM-killed).

If a workload tries to consume more CPU than is available, it will simply not receive as much CPU time as it wants, and will be throttled.

This distinction doesn’t really matter, for the purposes of this article, so we’re going to pretend we can treat memory and CPU exactly the same.

Namespace request limits

A namespace is the largest “unit of work” that the cluster needs to worry about.

When you create a namespace, the ResourceQuota specifies limits on the amount of resources that it will allow the namespace to request. This file defines the defaults we assign to new namespaces. The requests.cpu specifies the CPU resources, usually in millicores aka millicpus. requests.memory specifies the required memory, usually in mebibytes.

These values represent the amount of CPU and memory that the cluster will set aside as soon as this namespace is created, regardless of whether or not those resources are being used to do any useful work.

This means it is possible to run out of cluster resources before any work is actually performed, just by requesting (i.e. reserving) capacity.

For this reason, we need to be conservative when assigning request limits to namespaces. This won’t prevent your namespace from accessing resources that it needs, but a lower request limit will help us to use the capacity of the cluster more efficiently, to run everyone’s workloads.

Container request limits

The smallest unit of work the cluster cares about is a container.

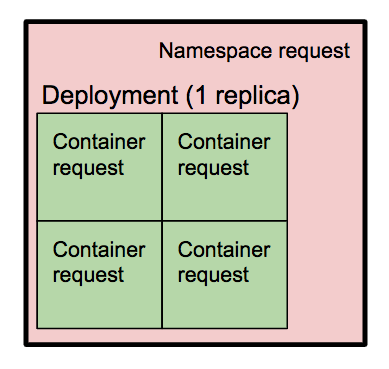

Kubernetes workloads are generally defined in terms of pods, where each pod defines a number of containers. Containers also have request limits and hard limits on the resources that will be set aside for them, or which they shouldn’t exceed.

Here is an example of a deployment template which specifies limits for the container it launches.

Whenever the scheduler tries to schedule a pod, it reserves whatever request limits are specified for each container. If the deployment doesn’t specify request limits for a given container, the default for the namespace will be used. This default comes from the namespace’s LimitRange. In our case, the default we apply for new namespaces is specified here.

The diagram above shows a namespace with a deployment consisting of four containers. If the service team wanted to run multiple replicas of this deployment, the scheduler would not allow it, because the namespace capacity limit (the pink square) is not enough to set aside the amount of resources that each of the containers say they want (the outer green square; i.e. you couldn’t fit another green square of that size inside the pink square).

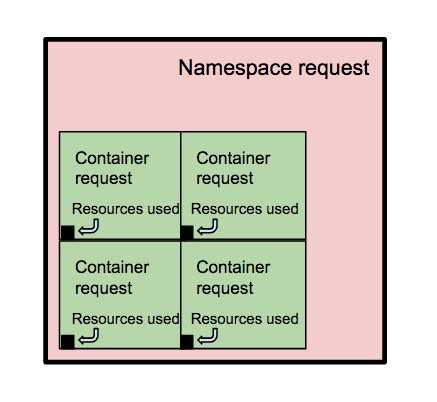

Resources Requested versus Resources Used

So far, we’ve only been talking about what resources we are requesting, and it’s clear that we can quickly run out of capacity in the cluster if we request too many resources. But how closely does what we request match what we use?

We have created this report that you can run to see how your namespace is doing (click on a namespace name to get more details. If yours is not visible, you can click on any namespace and replace the namespace name in the browser address bar to see yours).

Here is the current result (25/07/19) from running the script against the monitoring namespace (where things like prometheus and alert-manager run)

Namespace: monitoring

Request limit: CPU: 10000, Memory: 24000

Requested: CPU: 2215, Memory: 13115

Num. containers: 58

Req. per-container: CPU: 125, Memory: 250

Resources in-use: CPU: 363, Memory: 6795

CPU values are in millicores (m). Memory values are in mebibytes (Mi).

As you can see, we’re doing quite badly in terms of efficient usage of cluster resources. Inside the namespace, we’re requesting 2215 millicores of CPU, but only using 363, and we’re requesting 13115Mi of memory, but only using 6795Mi.

Worse still, we have a request limit of 10000m CPU and 24000Mi of memory (i.e. 10 CPU cores, and 25G of memory). Those resources have been set aside for the monitoring namespace, and are not available to run any other workloads.

If this pattern were to be repeated across all the namespaces in the cluster, we would have a serious problem. We can make the cluster bigger to get more capacity, and we have done so several times, but there are knock-on effects. The more cluster nodes we have, the harder the cluster control software has to work, and some functions get slower, or even stop working altogether, so more work has to be done to scale those up, and so on.

For this reason, we avoid specifying memory and CPU limits on namespaces, and our resource quota template merely limits the number of pods a namespace can launch. This has worked well so far, but if you have specific reasons why you need a different approach in your namespace, please start a discussion in the #ask-cloud-platform channel.